Popular as Uber may be, it isn’t the only way to summon a car for a ride across town. In most US cities, Lyft is a strong number two. Here in Boston, Fasten touts lower fees to drivers, promising cheaper rides for passengers and greater revenue to drivers. Drivers often run multiple apps, and passengers switch between them too. If these apps competed fiercely, Uber might be forced to lower its fee, reducing or eliminating profit. So what justifies Uber’s lofty $68+ billion valuation?

For years, Uber has tried to use its API as a potential barrier against competition. Uber invites third-party developers to connect to its servers to get real-time information about vehicle location (how many minutes until a vehicle can pick up a passenger at a given location) and the current level of surge pricing. But there’s a catch: To access data through Uber’s API, developers must agree not to include Uber API data in any tool that Uber deems competitive.

Uber encourages app developers and the general public to think this API restriction is Uber’s right—that Uber’s data is for Uber to use or restrict as it chooses. But the restriction is calculated and intended to block competition—a purpose considered improper under competition laws, and a special stretch for Uber in light of the company’s positions on related issues of competition and regulation.

Uber’s API restrictions

Uber’s API Terms of Use explains Uber’s purpose in remarkable simplicity:

Be a strong, trustworthy partner to Uber. Please do not:

Compete with Uber or try to drive traffic away from Uber.

…

Aggregate Uber with competitors.

Uber’s API Terms of Use then instruct:

In general, we reserve the sole right to determine whether or not your use of the Uber API, Uber API Materials, or Uber Data is acceptable, and to revoke Uber API access for any Service that we determine is not providing added benefit to Uber users and/or is not in the best interests of Uber or our users.

The following are some, but not all, restrictions applicable to the use of the Uber API, Uber API Materials, and Uber Data:

…

You may not use the Uber API, Uber API Materials, or Uber Data in any manner that is competitive to Uber or the Uber Services, including, without limitation, in connection with any application, website or other product or service that also includes, features, endorses, or otherwise supports in any way a third party that provides services competitive to Uber’s products and services, as determined in our sole discretion.

Uber’s developer documentation specifically warns:

Using the Uber API to offer price comparisons with competitive third party services is in violation of § II B of the API Terms of Use. Please make sure that you familiarize yourself with the API Terms of Use to avoid losing access to this service.

Assessing Uber’s API restrictions

The most favorable reading of Uber’s API restrictions is that Uber alone controls information about the price and availability of its vehicles. From Uber’s perspective, accessing Uber’s API is a privilege, not a right. Indeed, some might ask why Uber might be expected, let alone required, to assist a company that might send users elsewhere. A simple contract analysis shows no reason why the restriction is improper; if Uber prominently announces these requirements, and developers willingly accept, some would argue that there’s no problem.

A strong counterargument begins not with the contract but with Uber’s purpose. One might ask why Uber seeks to ban comparisons with other vehicle dispatch services. Uber doesn’t ban aggregators and price comparison tools because it believes these tools harm passengers or drivers. On the contrary, Uber bans aggregators and price comparison tools exactly because they help passengers and drivers but, potentially, harm Uber by directing transactions onto other platforms. Uber’s purpose is transparently to impede competition —to make it more difficult for competing services to provide relevant and timely offers to appropriate customers. Were such competitors to gain traction, they would push Uber to increase quality and reduce its fees. But blocking competing services positions Uber to retain and indeed increase its fees.

Consider a competitor’s strategy in attempting to compete with Uber: Attract a reasonable pool of drivers, impose a lower platform fee than Uber, and split the savings between drivers and passengers. If Uber’s current fee is, say, 20%, the new entrant might charge 10%—yielding savings which could be apportioned as a 5% lower fare to passengers and a 5% higher payment to drivers.

Crucially, aggregators help the entrant reach passengers at the time when they are receptive to the offer. Every user at an aggregator is in the market for transportation, not just generally but at that very moment, making them naturally receptive to an entrant’s offer. Furthermore, a user who visits an aggregator has all but confirmed his willingness to try an alternative to Uber. So aggregators are the most promising way for an entrant to reach appropriate users.

At least as important, aggregators help an entrant gain momentum despite a small scale of operations. At the outset, a new entrant wouldn’t have many drivers. So if a consumer installs the entrant’s app and opens it to check vehicle availability, the entrant’s proposed vehicle would often be further away, requiring that passengers accept longer wait times and that drivers accept longer unpaid trips to reach paid work. Notably, an aggregator helps the entrant reach users already close to the available vehicles—providing an efficient way for the entrant to begin service.

In contrast, without aggregators, entrants face inferior options for getting started. They could advertise in banners or on billboards to attract some users. But those general-purpose ad channels tend to reach a broad swath of users, only a portion of whom need Uber-style service, and even fewer of whom are ready to try a new service. Meanwhile, any users found through these channels will tend to have diverse requirements for ride timing and location; there is no way for an entrant to reach only the passengers interested in rides at the times and places where the entrant has available drivers. With a low density of drivers and passengers, the entrant’s passengers will face longer wait times and drivers will face longer unpaid positioning trips. Some users may nonetheless be willing to try the entrant’s service. But they’ll have to open the entrant’s app to check, for each trip, whether its availability and pricing meet expectations—extra steps that impose delay and will quickly come to seem pointless to all but the most dedicated passengers. As a whole, these factors reduce the likelihood of the new service taking off. Indeed, small transport services have famously struggled. Consider, for example, the 2015 cessation of Sidecar.

Uber might have tried to explain away its API restrictions with pretextual purposes such as server load or consumer protection. These arguments would have been difficult: Price comparison requests are not burdensome to Uber’s servers; Uber nowhere limits the quantity of requests for other purposes (e.g. through an API fee or through throttling). Nor is there any genuine contention that price comparison services are, say, confusing to users; the difference between an Uber and a Lyft ride can be easily communicated via an appropriate logo, on-screen messaging, and the like. But in any event Uber hasn’t attempted these arguments; as Uber itself admits in the rules quoted above, the API restrictions are designed solely to advance the company’s business interests by blocking competition.

The relevant legal principles

One doesn’t readily find antitrust cases about APIs or facilitating price comparison. But Uber’s API partners act as de facto distributors—telling the interested public about Uber’s offerings, prices, and availability. A long line of cases takes a dim view of dominant firms imposing exclusivity requirements on their distributors. Areeda and Hovenkamp explain the tactic, and its harm, in their treatise (3d ed. 2011, ¶1802c at 76):

[S]uppose an established manufacturer has long held a dominant position but is starting to lose market share to an aggressive young rival. A set of strategically planned exclusive-dealing contracts may slow the rival’s expansion by requiring it to develop alternative outlets for its product, or rely at least temporarily on inferior or more expensive outlets. Consumer injury results from the delay that the dominant firm imposes on the smaller rival’s growth.

Most recently, the FTC brought suit against McWane, the dominant US pipe fitting supplier, which had controversially required distributors to sell only its products, and not products from competitors, by threatening forfeiture of rebates and perhaps loss of access to any McWane products at all. The FTC found that McWane’s exclusionary distribution policy maintained its monopoly power; the Eleventh Circuit upheld the FTC’s finding; and the Supreme Court declined to hear the case. McWane thus confirms the competition concerns resulting from exclusive contracts from distributors. In relevant respects, the parallels between Uber and McWane are striking: Both companies use contracts to raise rivals’ costs to prevent them from growing into effective competitors. Compared to McWane, Uber’s API restrictions are in notable respects more aggressive. For example, McWane’s first response to a noncompliant distributor was to withhold rebates, and in litigation McWane protested that its practice was not literally exclusive dealing but rather a procompetitive inducement (through rebates yielding lower prices). Putting aside McWane’s failure in these arguments, Uber could make no such claims, as its API restrictions (and threats to UrbanHail, discussed below) exactly implement exclusive dealing, expelling the noncompliant app or site from access to Uber’s API as a penalty for including competitors.

More generally, Uber’s conduct falls within the general sphere of exclusionary conduct which has been amply explored through decades of caselaw and commentary. The Department of Justice’s 2009 guidance on Single-Firm Conduct Under Section 2 of the Sherman Act is broadly on point and usefully surveys relevant doctrines. As the DOJ points out, the essential question for exclusionary conduct cases is whether a given tactic is appropriate, aggressive competition (which competition policy sensibly allows) versus a practice intended to exclude competition (more likely to be prohibited under competition law). After considering several alternatives, the DOJ favorably evaluates a "no-economic-sense test" that asks whether the challenged conduct contributes profits to the firm apart from its exclusionary effects. In Uber’s case, no such profits are apparent. Indeed, the API restrictions require Uber to turn down referrals from apps that violate the API restrictions—foregoing short-term profits in service of the long-term exclusionary purpose.

The DOJ ultimately offers its greatest praise for an "equally efficient competitor test," asking whether the challenged conduct is likely in the circumstances to exclude a competitor that is equally efficient or more efficient. Uber’s restrictions fare poorly under this test. Consider a more efficient competitor—one with, perhaps, lower general and administrative costs that allow it to charge a lower fee on top of payments to drivers. Uber’s restrictions prevent such a competitor from effectively reaching the consumers who would be most receptive to its offer.

Separately, the DOJ notes the promise of conduct-specific tests that disallow specific practices. While the caselaw on APIs, data access, and price comparison is not yet well-developed, one might readily imagine a conduct-specific test in this area. In particular, if a company offers a standardized and low-burden mechanism for consumers, intermediaries, and others to check its prices and availability, the company arguably ought not be able to withhold access to that information for the improper purpose of blocking competition.

Relatedly, the DOJ points out the value of considering the scope of harm from the challenged conduct, impact of false positives and false negatives, and ease of enforcement. Uber’s restrictions fare poorly on these fronts too. Uber would face little burden in being required to provide data about its prices and availability to comparison services; Uber has already built the software interface to provide this data, and the servers are by all indications capacious and reliable. Enforcement would be easy: Require Uber to strike the offending provisions from its API Terms and Conditions. Uber need not create any new software interfaces or APIs in order to comply; only Uber’s lawyers, but not Uber’s developers, would need take action.

Uber might argue that it is one of many transportation services and that the Sherman Act should not apply given Uber’s small position in a large transport market. Indeed, Sherman Act obligations are predicated on market power, but Uber’s size and positioning leave little doubt about the company’s power. As the leading app-based vehicle dispatch service, Uber would certainly be found a dominant firm in such a market. In a broader market for hired transport services, including taxis and sedans, Uber surely still has market power. For example, analysis of expense reports indicates that business travelers use Uber more than taxis.

Experience of transport comparison services and the case of UrbanHail

As early as August 2014, analysts had flagged Uber’s restriction on developers promoting competing apps. Indeed, the subsequent two years have brought few apps or sites that help consumers choose between transportation platforms—some with static data or general guidance, but no widely-used service with up-to-the-minute location-specific data about surges and vehicle availability. Uber’s API restrictions seem to be working in exactly the way the company hoped.

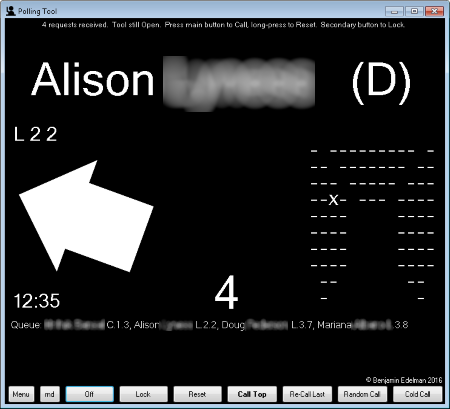

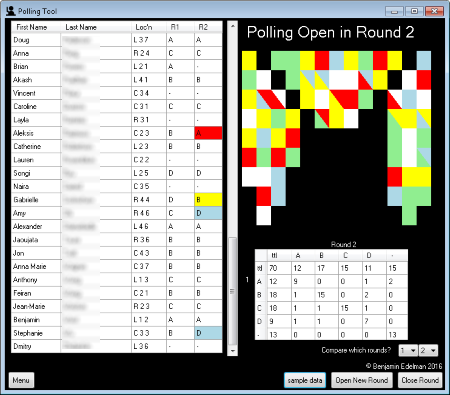

An intriguing counterexample comes from UrbanHail, an app which promises to present "all of your ridesharing and taxi options in one click to help you save time and money [and] frustration." (UrbanHail was created by five Harvard Business School MBA students as their semester project for the required FIELD 3 course. As part of my academic duties as a HBS faculty member, I happen to teach FIELD 3, though I was not assigned these students. I advised them informally and have no official academic, supervisory, or other affiliation with the students or UrbanHail.)

UrbanHail prompted a response from Uber the same day it launched. In a first email, Uber’s Chris Messina (Developer Experience Lead) wrote:

Hey guys, my name is Chris Messina and I run Developer Experience for Uber. Chris Saad [CC’ed] is the PM of the API.

We wanted to congratulate on your recent press as we love seeing folks innovating in the transit space, but wanted to let you know that your use of our API is in violation of section II B of our terms of use.

We’re more than happy for you to continue developing your app, but ask that you remove any features that list Uber’s prices next to our competitors.

Please let us know if you have any questions. Thanks!

Three weeks later, he followed up:

Hey guys,

I haven’t heard back from you, so I wanted to follow up.

Unfortunately, UrbanHail is still violating the agreements you entered with Uber, including not only the API Terms of Use which I mentioned in my previous email, but also Uber’s rider terms (which prohibit scraping or making Uber’s services available for commercial use).

I’d like to highlight that not only are these conditions found in the legal text, but the spirit of our terms are summarized in plain english at the top of that document. Further, a specific warning to not create a price comparison app is provided in-line in the technical reference for the price estimates API.

Thousands of developers around the world use the Uber API to build new, interesting apps. To preserve the integrity of the Uber experience, we require these apps to stay within the guardrails we’ve created, and are set forth in our terms. Despite our efforts to make these terms and policies clear and transparent, you chose to act against them.

All that being said, we very much value the time and energy that developers like you invest in building with the Uber API, and we actively support and encourage them to be creative and innovate with us.

If you build something that complies with our Terms of Use, we would love to reward your effort in a number of ways. Here are just some of the things we can offer:

* A post on our blog featuring your app

* A listing in our showcase

* Affiliate revenue for referring new Uber riders to us

* Access to our "Insiders Program" which offers office hours with the Uber Developer Platform team and exclusive developer events

Please let me know when you’ve taken UrbanHail out of the App Store and removed any related marketing materials so we can start working on a new opportunity together.

Please note, however, if I don’t hear from you by May 31, I’ll be forced to revoke your client ID’s access the Uber API.

Chris

Today, May 31, is Chris’s deadline. I’ll update this post if Chris follows through on the threat to disable UrbanHail’s API access and prevent the app from including Uber in its price comparison.

Update (June 3): UrbanHail reports that Uber terminated its API access, preventing Uber from appearing within Urbanhail’s results page.

Special challenges for Uber in imposing these restrictions

Uber styles itself as a champion of competition. Consider, for example, CEO Travis Kalanick’s remarks to attendees at TechCrunch Disrupt in 2012. His bottom line: "Competition is good." Uber takes similar positions in its widespread disputes with regulators and incumbents transportation providers—styling its offering as important competition that benefits consumers. Against that backdrop, Uber struggles to restrict third-party services that promise to enhance competition.

Indeed, media coverage of Uber’s dispute with UrbanHail has flagged the irony of Uber criticizing competition from other services. The Boston Globe captioned its piece "New app gives Uber a little disruption of its own," opening with "Uber Technologies Inc. built a big business by pushing past regulations that limit competition with taxis. But the tech-industry darling isn’t always happy with smaller companies trying similar tactics." Boston.com was in accord: "Uber rankled by app that compares ride-hailing prices," as was BostInno: "Uber is trying to shut down this Boston price-comparison app."

Twitter users agreed: Henry George: "@Uber Do you find it the least bit ironic that you’re complaining about ride competition with @urbanhail? Don’t try legal BS, innovate!" Michael Nicholas: "The irony of @Uber complaining @urbanhail is breaking the rules’ of api usage is breathtaking." Gustavo Fontana: "@Uber should leave them alone. It’s fair game."

Uber may dispute whether it has the market power necessary to trigger antitrust law and Sherman Act duties. But Uber’s general position on competition is clear. Uber struggles to chart a path that lets it compete with taxis without the permits and inspections required in many jurisdictions—but doesn’t let comparison shopping services compare Uber’s prices with taxis, Lyft, and other alternatives.

Moreover, Uber’s professed allies are equally difficult to reconcile with the company’s API restrictions. For example, Uber this month announced an advisory board including distinguished ex-competition regulators. Consider Neelie Kroes, formerly the European Commission’s Commissioner for Competition who, in that capacity, oversaw the EC’s €497 million sanctions against Microsoft. Having overseen European competition policy and subsequently digital policy for fully a decade, Kroes is unlikely to look favorably on Uber’s efforts to foreclose entry and reduce competition.

Special challenges for Uber’s developer team in imposing these restrictions

A further challenge for Uber is that its key managers—distinguished experts on software architecture—have previously taken positions that are difficult to reconcile with Uber’s efforts to restrict competition.

Best known for creating the hashtag, Chris Messina (Uber’s Developer Experience Lead) boasts a career espousing "openness." In his LinkedIn profile, he notes a prior position as an "Open Web Advocate" and a board member at the "Open Web Foundation." Describing his work at Citizen Agency, he says he "appl[ied] design and open source principles to consulting." Wikipedia disambiguates Messina from others with the same name by calling him an "open source advocate," a phrase repeated in the first sentence of Wikipedia’s article. Wikipedia also notes a 2008 article entitled "So Open It Hurts" about Messina and his then-girlfriend, describing their "public and open relationship." Google reports 1,440 different pages on Messina’s personal site, factoryjoe.com, mentioning the word "open." While the meaning of "open" varies depending on the context, the general premise is a skepticism towards restrictions and limitations—be they requirements to pay for software, limits on how software is used, or, here, restrictions on how data and APIs are used. It’s a world view not easily reconciled with Uber’s restriction on price comparisons.

Chris Saad (Uber’s API Product Manager) has been similarly skeptical of restrictions on data. His LinkedIn page notes that he co-founded the DataPortability Project which he says "coined and popularized the phrase "data portability"; and led "an explosion of conversation[s] about open standards and interoperability." That’s a distinguished background—but here, too, not easily reconciled with Uber’s API restrictions.

It’s no coincidence that Uber’s developer team favors openness. Openness is the natural approach as a company seeks to connect to external developers. But in limiting how other companies use data, Uber violates key tenets of openness, restricting the flow and use of data that partners and consumers reasonably expect to access.

Looking ahead

Uber faces a looming battle to retain its early lead in smartphone-based vehicle dispatch. But as the dominant firm in this sector—with the largest market share and, to be sure, a category-defining name and concept—Uber is rightly subject to restrictions on its methods of competition. Cloaking itself in the aura of competition as it seeks to avoid regulations that apply to other commercial vehicles, Uber is poorly positioned to simultaneously oppose competition from other app-based services.

Uber is not alone in limiting the ways users can access data. In 2008, I flagged Google’s AdWords API restrictions, which impeded advertisers’ efforts to use other ad platforms as well as Google. Google defended the restrictions, but competition regulators agreed with me: Even as the FTC declined to pursue other aspects of early competition claims against Google, FTC pressure compelled Google to withdraw the API restrictions in January 2013. In Europe, these same restrictions were among the EC’s initial objections to Google’s conduct. Google has yet to resolve this dispute in Europe, and may yet face a fine for this conduct (in addition to substantial fines for other challenged practices). Uber’s API restrictions risk similar sanctions—perhaps even more quickly given Uber’s many regulatory proceedings.

What comes next? If Uber follows through on its threat to UrbanHail, as Messina said it soon would, there will again be no app or site to compare prices and availability across Uber and competitors. Uber won’t need to go to court to block UrbanHail; it can simply withdraw the security credentials that let UrbanHail access the Uber API. From what I know of UrbanHail’s size and stature, it’s hard to imagine UrbanHail filing suit; that would probably require resources beyond UrbanHail’s current means.

Nonetheless, Uber is importantly vulnerable. For example, transport is highly regulated, and Uber needs regulatory approval in most jurisdictions where it operates. This approval presents a natural and easy way for policy makers to unlock Uber’s API restrictions: As a condition of participation in a city’s transit markets—using the public roads among other resources—Uber should be required to remove the offending API restrictions, letting aggregators use this information as they see fit. Once one city establishes this requirement, dozens more would likely follow, and Uber’s API restrictions could disappear as suddenly as they arrived.