On December 21, YouTuber MegaLag dropped a 23 minute video eviscerating Honey. Calling Honey a “scam”, he made two core allegations.

-

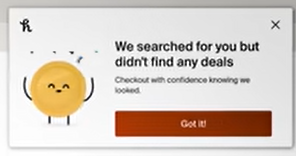

Honey claims affiliate commission if a user presses “Got it” to acknowledge no deal found Honey takes payments that would otherwise go to influencers who recommended products users buy. (video at 2:50) MegaLag shows Honey claiming payments in four scenarios: i) if a user activates a function to search for coupons (even if none are found), ii) if a user activates a function to claim Honey Gold (no matter how meager the rebate), iii) if the user gets the message “We searched for you but didn’t find any deals” and merely presses the button “Got it”, and iv) If Honey shows the message “Get Rewarded with PayPal” “Shop eligible items to earn cash off future purchases” and the user presses “checkout”.

- Honey doesn’t actually get the best deals for users. If a merchant joins Honey (and begins to pay Honey affiliate commissions), Honey allows the merchant to limit which coupons Honey shows to users. MegaLag points out that letting merchants remove discounts from Honey is squarely contrary to Honey’s promise to users that it will find “the Internet’s best discount codes” and “find every working promo code on the Internet.” (video at 16:20)

16 million views and growing, MegaLag’s video has prompted a class action lawsuit and millions of users uninstalling Honey.

I’m a big fan of MegaLag. I watched most of his other videos, and they’re both informative and useful—for example, testing Apple AirTags by intentionally leaving items to be taken; exploring false claims by DHL about both package status and their supposed investigations. Meanwhile, nothing in MegaLag’s online profile indicates prior experience in affiliate marketing. But for a first investigation on this subject, he gets most things right, and he uses many appropriate methods including browser dev tools and screen-capture video. Based on its size and its practice, Honey absolutely deserves the scrutiny it’s now getting. Kudos to MegaLag.

Nonetheless there’s a lot MegaLag doesn’t say. Most notably, he doesn’t mention contracts—the legal infrastructure that both authorizes Honey to get paid and sets constraints on when and how it may operate. Furthermore, he doesn’t even consider whether merchants get good value for the fees they pay Honey. In this piece, I explore where I see Honey most vulnerable—both under contract and for merchants looking to spend their marketing funds optimally.

The contracts that bind Honey

Affiliate marketing comprises a web of contracts. Most affiliate merchants hire a network to track which affiliate sent which traffic, to provide reports to both merchant and publishers, and to handle payments. For a single affiliate-merchant relationship, an affiliate ends up subject to at least two separate contracts: the network’s standard rules, and any merchant-specific rules. Of course there are tens of thousands of affiliate merchants, and multiple big networks. So it’s impossible to make a blanket statement about how all contracts treat Honey’s conduct. Nonetheless, we can look at some big ones. Numbering added for subsequent reference.

Commission Junction Publisher Service Agreement

C1 “You must promote Advertisers such that You do not mislead the Visitor”

C2 “the Links deliver bona fide Transactions by the Visitor to Advertiser from the Link”

C3 “You must accurately, clearly and completely describe all promotional methods by selecting the appropriate descriptions and providing additional information when necessary.”

C4 “You agree to: (i) use ethical and legal business practices”

C5 “Software-based activity must honor the CJ Affiliate Software Publishers Policy requirements (as such requirements may be modified from time to time), including but not limited to: (i) installation requirements, (ii) enduser agreement requirements, (iii) afsrc=1 requirements, (iv) requirements prohibiting usurpation of a Transaction that might otherwise result in a Payout to another Publisher (e.g. by purposefully detecting and forcing a subsequent click-through on a link of the same Advertiser) and (v) non-interference with competing advertiser/ publisher referrals.”

Rakuten Advertising Downloadable Software Applications (DSAs) Overview, Testing Process, Policies

R1 “Your DSA should become inactive on the sites of any advertisers who opt-out or stand down on those that do not want you to redirect their traffic. Publishers who fail to comply with this rule will jeopardize their relationship with advertisers as well as with Rakuten Advertising.”

R2 “[W]e expect your DSA to: Stand down when it recognizes any publisher links”

R3 “[A]ll software must recognize Supplier domains and the linksynergy tracking links. When a Supplier domain or the linksynergy code is detected, the software may not operate or redirect the consumer to the advertiser site using the Software Publisher tracking ID (also known as Supplier Affiliate ID or Encrypted ID). We do not allow any DSA software that interferes with or deters from any Publisher or Advertiser website.”

R4 “The DSA must stand-down and not display any forms of sliders or pop-ups to prompt activation if another publisher has already referred an end user.”

R5 “The DSA must not force clicks or “cookie stuff”. The DSA must not insert a cookie onto the user’s computer without the user knowingly taking an action that results in the cookie being placed.”

R6 “The end user must click through the offer that is presented. Placing the mouse over an offer, only viewing it or viewing all offers is not a click through.”

R7 “The DSA must not automatically drop a cookie when the end user is only viewing offers. The cookie should only be dropped once the end user clicks on a specific offer.”

Awin including ShareASale – Code of Conduct, Awin US Publisher Terms, SAS US Publisher Agreement

A1 “’Click’ means the intentional and voluntary following of a Link by a Visitor as part of marketing services as reported by the Tracking Code only;”

A2 “Publishers only initiate tracking via a tracking link used for click tracking if the user voluntarily and intentionally interacted with the Ad Media or Tracking link.”

A3 Publishers only initiate tracking for a specific advertiser if the consumer interacted directly with ad media for this advertiser.”

A4 ”do not mislead consumers”

A5 “transparency about traffic sources and the environment that ads are displayed in”

In addition, all networks indicate that publishers must disclose their practices to both networks and merchants. Awin Code of Conduct is representative: “Publishers proactively disclose all promotional activities and obtain advertiser approval for their activities.” Rakuten’s Testing Process is even more prescriptive, requiring an affiliate both to submit a first version and to notify Rakuten about any changes so it can retest; plus requiring publishers to answer 16 questions about their software including technical details such as DOM ID and Xpath of key functions.

Honey violates network policies

MegaLag’s video show violations of these network policies. I see three clusters of violations.

(1) Honey invokes its affiliate links although users did not fairly request any such thing. Consider “We searched for you but didn’t find any deals” with button labeled “Got it” (MegaLag scenario iii above). “Got it” doesn’t indicate that the user wants, expects, or agrees that Honey will invoke its affiliate link. That’s certainly misleading (contrary to rule C1). Nor can Honey claim that a user who clicks “Got it” is “knowingly taking an action that results in the cookie being placed” (R5) because clicking “Got it” isn’t the kind of action that rule contemplates. Rakuten rules R6 and R7 are equally on point, disallowing invoking an affiliate link based on an activity that doesn’t indicate intent (such as a mouseover), and requiring that an affiliate link only be invoked “once the end user clicks on a specific offer.” “Got it” isn’t an offer, so under R7, that’s not grounds for invoking a Rakuten link. So too for Awin, where A1 defines “click” to include only links that are “part of marketing services” (but “Got it” is not marketing service). See also A2 and A3 (allowing links only as part of “ad media”, but “Got it” is not ad media); and of course A4 (“do not mislead consumers”).

Honey’s invocation of affiliate links upon a “Get rewarded with PayPal” message (MegaLag scenario iv above) is on similarly shaky ground. For example, responding to a PayPal offer is not “knowingly taking an action that results in the cookie being placed” (R5) – the user knows only that he’s closing the message, not that he’s requesting an affiliate referral back to the merchant. Similarly, a PayPal offer is not “marketing services” or “ad media” for an Awin merchant (rules A1-A3).

The rule to invoke affiliate links only when a user so requests is no mere technicality. In affiliate marketing, an affiliate may be paid if 1) the user sees a link, 2) the user clicks the link, and 3) the user buys from the specified merchant. Skipping step 2 sharply increases the circumstances in which a merchant has to pay commission—not a term a merchant would agree to. When an affiliate skips step 2, it’s cookie-stuffing. Publishers have gone to jail for this (and had to pay back commissions received). Honey didn’t quite stuff cookies as that term is usually used—the user did click something. But when nothing on the button (not its label, not the surrounding message, not any principle of logic or engineering) indicates or even suggests the button will activate an affiliate link—that’s terrible value for the merchant.

(2) Honey presents its affiliate links although a user recently clicked through another publisher’s offer. (MegaLag at 2:50) But networks’ rules require Honey to stand down if another publisher has made a referral. See rule C5.v (“non-interference with competing advertiser/ publisher referrals”) and R2 (“Stand down when it recognizes any publisher links”). Rakuten even makes explicit that the stand-down obligation applies not just to automatic clicks (which, uh, aren’t permitted in any event) but also to sliders and popups: “The DSA must stand-down and not display any forms of sliders or pop-ups to prompt activation if another publisher has already referred an end user.” (R4)

Here too, this is no technical violation. Other publishers need “stand down” rules so they have a fair chance to earn commission for their work promoting a given merchant. Standing down from another affiliate’s click is the most fundamental affiliate network rule for downloadable software and browser plug-ins.

(3) Honey falls short of disclosure obligations. “You must accurately, clearly and completely describe all promotional methods by selecting the appropriate descriptions and providing additional information when necessary” (C3). Publishers must provide “transparency about traffic sources and the environment that ads are displayed in” (A5). I’m open to being convinced that Honey told networks and merchants it would invoke affiliate links with buttons as weakly labeled as “Got it.” I don’t buy it. Merchants have a clear contractual basis to expect complete and forthright disclosures—it is literally their money being paid out. And merchants authorized networks to collect and evaluate these disclosures for them. No shortcuts.

One might object that networks can waive rules or create exceptions for key partners. Not so fast! Merchants and publishers rely on networks to enforce their published rules exactly as promised. In fact, in 2007, both merchants and publishers sued ValueClick to allege that it had been less than diligent in enforcing its rules. ValueClick’s Motion to Dismiss argued that it could do what it wanted, that it had disclaimed all warranties, and that it made no promises that merchants or publishers were entitled to rely on. But the court denied ValueClick’s motion, eventually yielding a settlement requiring both improved efforts to detect affiliate fraud as well as certain refunds to merchants and payments to publishers. There’s room to disagree about how much benefit the settlement delivered. (Maybe the settlement promised changes that ValueClick was going to do anyway. Maybe the monetary payments were a small fraction of the amount lost by merchants and publishers.) But the fundamental principle was clear: Networks must follow their contractual representations including policies about prohibited behaviors. And while networks may try to disavow quality responsibilities, for example via disclaimers in contracts, courts are skeptical of the unfettered discretion these provisions purport to create. A network that promises to track affiliate transactions ultimately ought to do so accurately, and should neither grant arbitrary waivers nor look the other way about serious misconduct.

How did we get here?

Honey’s one-sentence response to MegaLag was “Honey follows industry rules and practices, including last-click attribution.” It’s no surprise that Honey claims compliance. But I was surprised to see affiliate thought-leaders agree. For example, long-time affiliate expert Brook Schaaf remarked “Honey appears to be in compliance with network standards.” Awin CEO Adam Ross says MegaLag’s video “portray[s] performance marketing attribution as a form of theft or scam”—suggesting that he too thinks Honey did nothing wrong.

I’ll update this piece with when others dig into the contracts and compare Honey’s practices with the governing requirements. But after more than 20 years working on affiliate fraud—my first piece on this subject was, wow, 2004—let me offer four observations.

One, it’s easy to get complacent. Much of what Honey does is distressingly normal among browser extensions. Test the Rakuten Cashback app and you’ll find much the same thing. Above, I linked to litigation against Honey, but there’s also now similar litigation against Capital One, alleging that its Capital One Shopping browser extension is out of line the same way as Honey. Brook and Adam are right that Honey’s tactics aren’t a surprise to anyone who’s been in the industry for decades. Many people have come to accept behaviors that don’t follow the literal meaning of stated policies. Some would say the policy is out of date. I’d say, instead, that key decision-makers have been asleep at the switch.

Two, networks’ incentives are mixed. On one hand, networks want affiliate marketing to be seen as trusted and trustworthy, which requires eliminating practices widely seen as unfair. At the same time, affiliate networks typically charge a commission on every dollar of commission paid. As a result, networks directly benefit from anything that increases the number of dollars of commission paid—such as allowing browser plug-ins to change non-commissionable traffic into commissionable traffic. Merchants should be skeptical of networks too quickly declaring traffic compliant when networks literally get paid for that finding. With Rakuten operating both a cashback service (with browser plugin) and an affiliate network, their incentives are particularly muddy: If Rakuten Advertising declares a given browser plugin tactic to be permitted, Rakuten Cashback can then use that tactic, increasing both Cashback fees (the Cashback margin on each dollar of rebate) and Advertising fees (the network margin on each dollar of affiliate activity). I like and respect Rakuten and its leaders, but their complicated incentives mean serious people should give their pronouncements a second look.

Three, most people read the governing contracts hastily if at all. I’m proud to have pulled out the 17 rules above, and I encourage readers to follow my links to see these and other rules in the larger policy documents. Fact is, there’s lots of material to digest. I’ve found that networks’ compliance teams often build rules of thumb that diverge from what the rules actually say, and ignore rules that are in some way seen as inconvenient or overly restrictive. That’s a mistake. The rules may not be holy, but they have the force of contract, and there’s real money at issue. Importantly, networks are spending other people’s money—making sure normal publishers get every dollar they fairly earned; and making sure merchants pay the correct amount, but not a penny more. This calls for a high level of care. We’re two weeks into the response to MegaLag. How many people posted video-responses, blogs, or other remarks without finding, reading, and applying the governing policies?

Four, personalities and work styles invite even merchant staff to accept what Honey is doing. Representative short-hand: “Go along to get along.” Most marketers chose this line of work to make connections, not to play policeman. Attend an affiliate marketing conference and you’re a lot more likely to see DJs and beer (party!) than network sniffers and virtual machines (forensic tools). Meanwhile, it’s awfully easy for an affiliate manager to tell a boss “we’re working with Honey, the billion-dollar product from PayPal”—then head to the Honey gala at an industry conference. Conversely, consider the affiliate manager who has to explain “we wasted $50k on Honey last month.” People have been fired for less. Ultimately, online marketing plays a procurement function—trying to spend an employer or client’s money as skillfully as possible, to get as much benefit as possible for as little expense as possible. That’s hard work, and I don’t fault those who want an easier path. I also don’t fault those who prefer the networking and gala side of marketing over the software forensics. Nonetheless, collective focus on the fun stuff goes a long way towards explaining how problems can linger (and grow).

Is Honey profitable for merchants?

For a merchant evaluating Honey, the fundamental question is pretty simple: Does Honey bring the merchant incremental sales and positive ROI? Clearly Honey’s browser extension positions it to claim credit on purchases users were already going to make, but incremental sales are what matter to merchants—purchases made only thanks to Honey.

My hypothesis is that Honey is ROI negative for most merchants. If a user goes to (say) dell.com, the user is already interested in Dell. Why should Dell let Honey’s browser plug-in jump in and claim a commission on that user’s purchase? Maybe Honey will increase the user’s conversion rate from 5% to 5.1% (by proclaiming what a good deal the user has found, or by touting a Honey Gold sweetener). But with payment to Honey, Dell’s margin will drop from (say) 7% to 5%. Would Dell prefer 7% profit on 500 sales, or 5% profit on 510? That math is pretty easy.

Of course the numbers in the preceding paragraph are just hypotheticals. If users sufficiently trust Honey (whether correctly or otherwise), their conversion rate might increase enough to justify Honey’s fees to merchants. If Honey could somehow persuade users to spend more—“add one more item to your cart, and you can get this $10 coupon”—that could increase value to merchants too (though I’ve never seen Honey deliver such a message). Some merchant advisors think this is plausible. I have my doubts.

Alarmingly, many merchants decide to work with Honey (and other “loyalty” software) without rigorously measuring incrementality (or even trying). Most merchants take some steps to measure the ROI of search and display ads. For years, affiliate ROI has been more challenging. But I recently devised a rigorous method that’s doable for most merchants. I’d enjoy discussing with anyone interested. When I have findings from a few merchants, with their permission I’ll share aggregate results.

Looking ahead

It’s easy to watch MegaLag’s piece and come out sour on affiliate marketing. (“What a mess!”) For that matter, the affiliate marketing section of my site has 28 articles over 20+ years, almost all about some violation or abuse.

Yet I am fundamentally a fan of affiliate marketing. Incentives aren’t perfectly aligned between affiliate, network, and merchant, but they’re a whole lot closer than in other kinds of online advertising. One twist in affiliate is that when a rogue affiliate finds a loophole, they can often exploit it at scale—by some indications, even more so than in other kinds of online advertising. Hence the special importance of networks and merchants both providing fairness and being perceived as providing fairness. MegaLag’s critique of Honey shows there’s no shortage of work to do.

Alexa reports a sharp jump in Blinkx traffic in late 2013.

Alexa reports a sharp jump in Blinkx traffic in late 2013.

IAC ad promises “free online television” but actually merely links to material already on the web; promises an “app” but actually provides a search toolbar.

IAC ad promises “free online television” but actually merely links to material already on the web; promises an “app” but actually provides a search toolbar.