When advertisers measure the effectiveness of their pay-per-click ad campaigns, advertisers systematically assume additionality, i.e. that the sales that follow a paid click are sales that would not have happened without the ad platform’s assistance. This assumption offers intuitive appeal: If a user clicked an ad and then bought the advertised product, by all indications the ad platform should be thanked for finding and sending an interested customer. Or should it?

As it turns out, Google and its partners systematically inflate advertisers’ conversion rates by interceding in transactions advertisers would otherwise have received for free. This conversion-inflation syndication fraud overstates the true effectiveness of the ads Google delivers — leading advertisers to pay more than they should.

In this piece, I offer four examples of Google and its partners inflating conversions to claim credit for traffic advertisers would otherwise have received for free. In each example, an advertiser intensely measuring its conversion rate would mismeasure the true effectiveness of its ads, and would end up overpaying for traffic that is far less valuable than reporting systems suggest.

| Traffic source |

How users are found |

What would have happened had Google and its partners not interceded |

| WhenU – adware |

User requests advertiser’s site. Adware covers advertiser’s site with pay-per-click listings. |

Advertiser’s site displays as usual, with no covering popup. User stays at advertiser’s site, and advertiser pays no PPC fee. |

| SmileyCentral – toolbar |

Reconfigured browser tricks user into running a “search” for a site’s domain name. |

User’s browser retains its ordinary configuration. User runs a direct navigation, and advertiser pays no PPC fee. |

| Typosquatting |

User misspells advertiser’s domain name. |

User’s browser shows a list of alternatives, and user selects one — reaching advertiser’s site at no charge. Or, user sees an error page, notices the misspelling, and corrects the spelling to reach the advertiser’s site without a PPC fee. |

| Chrome – browser suggestions |

User typing a web address is encouraged to run a search instead. |

User finishes typing the site’s web address and reaches the advertiser’s site without a PPC fee. |

WhenU Covers Advertisers’ Sites with Advertisers’ Own Google Ads

WhenU covers RCN with its own Google ads — chargingad fees for traffic RCN would otherwise have received for free.

WhenU covers RCN with its own Google ads — chargingad fees for traffic RCN would otherwise have received for free.

The money trail – how funds flow from advertisers

to Google to WhenU.

Through popups shown to users already at advertisers’ sites, WhenU (and its partners) charge advertisers for traffic they would have otherwise received for free. Google passes along these clicks through its advertising platform, and Google charges advertisers as if these were genuine leads, even though in fact these users were already on advertisers’ sites.

In testing of May 9, 2009, I browsed the web site RCN.com. Advertising software (generously, “adware”) from WhenU popped open the window shown at right — covering more than 80% of the RCN site with a list of pay-per-click ads, among them a prominent ad for RCN. I clicked the RCN ad, and I was taken back to RCN. See screenshots detailing the full sequence, or a screen-capture video.

As a provider of high-speed Internet access (with attendant concerns for user security, PC reliability, and tech support expense), RCN is unlikely to advertise with a notorious adware program like WhenU. Nor is RCN likely to want to show its ads to users already at rcn.com — users who RCN has already managed to reach. So how did RCN’s ads end up in this unfortunate placement? Using a network monitor, I confirmed the full sequence of intermediaries: WhenU and its MediaTraffic ad system sent traffic to LocalPages, which redirected to Nbcsearch, which forwarded the traffic to Infospace, which finally passed the traffic to Google. Google in turn paid Infospace, which paid Nbcsearch, which paid LocalPages, which paid WhenU. See the diagram at right and the full packet log.

For RCN, this placement is a rotten deal. RCN has already paid to get a user to its site — perhaps via a postcard, TV advertisement, display ad, or other paid search activity. But then WhenU intercedes and puts a roadblock in front of that user, in the form of the popup at right. A typical user presented with that popup will click the RCN entry to get back to RCN and continue the signup process. But then RCN pays twice to reach a single user.

Meanwhile, if RCN is tracking conversion rates, it will notice that this WhenU/Google placement seems to have a high conversion rate — reflecting that this ad was shown to users already on the verge of signing up with RCN. So in all likelihood, RCN will increase its Google bid to attempt to obtain more traffic of similar (apparent) quality. But the supposed high conversion rate is misleading at best: Since these are users who were already at the RCN site, without any intervention by Google or WhenU, it is nonsense to credit Google or WhenU for resulting sales.

This ad placement also lacks the labeling required by FTC policy and precedent. For one, all sponsored search ads are to be labeled as such, pursuant to the FTC ‘s 2002 instructions. But look closely at the popup screenshot. On my ordinary 800×600 screen, no such label appears. Furthermore, the FTC’s Direct Revenue and Zango complaints, decisions, and orders reveal an additional duty that adware vendors specifically and clearly label each popup with, among other information, a statement that the popup is an advertisement. (See Direct Revenue Decision and Order, provision VI.(1), and Zango Decision and Order, provision VI.(1).) Here, the popup bears the WhenU icon and even a phone number, but it lacks any disclosure that the window’s listings are advertisements. I gather the required label would ordinarily appear on a sufficiently large screen, but the FTC’s policies make no exceptions for users with small screens. Indeed, as netbooks gain popularity, small screens are increasingly common.

These ad placements are particularly troubling because they have continued for months on end. I first observed substantially similar placements on February 7, 2009, though I have reason to think the placements began well before then. Furthermore, Google has been on actual notice of these practices for 3+ months: I first reported these placements to the public in my lunch keynote at the INTA Trademark Law and the Internet conference on February 10, 2009. I posted my slides that very day, and slides 23-24 show substantially this same set of relationships. Importantly, Google’s Rose Hagan, Senior Trademark Counsel, was present in the audience, and she responded to this portion of the talk by promising to investigate. But despite her presence, my clear posting of the parties responsible, and a three month opportunity to act, Google has nonetheless failed to sever these relationships.

Plenty more could be said about WhenU. I have personally observed a wide variety of deceptive WhenU installations, including even WhenU installations via security exploits. (I never had occasion to post those videos to my public site, but I have them on file.) The Google-funded StopBadware declared multiple WhenU-bundlers to be “badware” (1, 2, 3) based on WhenU’s automatic startup, disruptive pop-ups, and other “bad or undisclosed” behaviors. But I doubt Google will defend its WhenU placements, so I’ll save full critique of WhenU for another day.

IAC’s SmileyCentral Grabs Advertisers’ Organic Traffic to Show Google Ads

Standard web browsers place a search bar at top-left. Click that box, type an address, and press enter to reach a site.

With SmileyCentral installed, a “direct navigation” request for www.verizon.com yields search results, not the Verizon site.

With SmileyCentral installed, a “direct navigation” request for www.verizon.com yields search results, not the Verizon site.

PPC advertisers (e.g. Verizon)

money

viewers

viewers

Google

money

viewers

viewers

IAC/SmileyCentral

The money trail – how funds flow from advertisers

to Google to IAC/SmileyCentral.

By reconfiguring users’ web browsers, IAC’s SmileyCentral toolbars charge advertisers for traffic they would otherwise have received for free. Google passes along these clicks through its advertising platform, and Google charges advertisers as if these were genuine leads, even though in fact these are users who were specifically and unambiguously trying to reach advertisers’ sites directly.

Since the earliest web browsers, a user seeking a particular web site clicks in the browser’s upper-left text box, types the desired address, and presses Enter. See the first inset image at right — standard Internet Explorer 6, offering exactly this layout to request a site.

But suppose a user installs the “SmileyCentral” toolbar from IAC (the advertising powerhouse that also owns Ask.com, Match.com, and more). SmileyCentral modifies longstanding browser layout by pushing a user’s Address Bar to the right, and inserting at left a search box where users naturally expect the Address Bar to appear. Then, when a user goes to the top-left box and enters a domain name, seeking a direct navigation to the specified site, SmileyCentral runs a search instead. See the second inset image at right — the result of typing www.verizon.com, then pressing Enter, into the top-left box. Notice that the user receives a list of search ads for Verizon, even though the user asked for Verizon by its correct web address.

IAC/SmileyCentral’s search results increase advertisers’ costs. Consider user behavior upon reaching the listings shown at right. In all likelihood, a user facing these listings will click one of the top links — perhaps the first listed (to verizonwireless.com) or the second (which specifically indicates it is the “Verizon Official Site”). But these are sponsored links. Every time a user clicks one of these links, Verizon pays a fee to Google, which in turn pays IAC/SmileyCentral. (To confirm Google’s role, see the packet log.)

As in the WhenU example above, this placement is a bad deal for advertisers. Had it not been for IAC/SmileyCentral’s tricky toolbar, these users would have directly reached the sites they requested. Instead, IAC/SmileyCentral grabs the users and sends them to lists of ads — saddling advertisers with unnecessary advertising expense.

Here too, advertisers are likely to be tricked if they attempt to assess the value of this traffic based on its conversion rate. The conversion rate may well be high — for these users asked for advertisers by name, suggesting that the users are nearly ready to make purchases. But the traffic is still a bad deal for advertisers: By all rights, this is still traffic advertisers should have gotten for free.

This placement is all the worse for advertisers because IAC makes ad clicks excessively easy. Even a click 230 pixels to the right of a Verizon Wireless ad would be treated as a paid click “on” that ad. See video at 0:23, and accompanying screenshot, showing that the hyperlink area extends far beyond the text of the ad.

IAC may claim that users understand that, with MyWebSearch installed, the top-left box no longer allows direct navigations by domain name or URL. But IAC often sneaks its toolbars onto users’ computers in ways that don’t obtain meaningful consent: I previously demonstrated nonconsensual installations through security exploits and undisclosed bundles. IAC’s installations often target kids (as I have repeatedly documented). And even a direct installation from Smileycentral.com places a picture of the post-installation browser layout in a bottom-of-page image, below the fold on 800×600 screens and easily overlooked on larger screens. IAC’s use of the generic “My Web Search” label (just as in “My Documents”, “My Computer”, etc.) further compounds users’ sense that this box is part of Internet Explorer. Combining IAC’s user focus with its choice of labeling and positioning, IAC creates conditions in which users are bound to be confused.

Typosquatting: Cmcast.com, MediaLogik, and Thousands More Intercept Users’ Misspellings to Show Google Ads

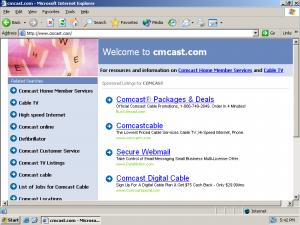

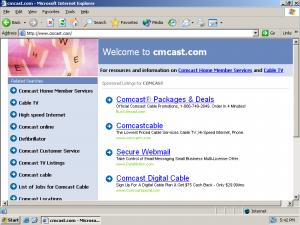

Requesting cmcast.com (s.i.c.) yields a page of Google ads.

If no typosquatter had registered cmcast.com, a user would have reached this page and found Comcast without charge.

If no typosquatter had registered cmcast.com, a user would have reached this page and found Comcast without charge.

PPC advertisers (e.g. Comcast)

money

viewers

viewers

Google

money

viewers

viewers

Typosquatters & brokers (e.g. MediaLogik)

The money trail – how funds flow from advertisers

to Google to typosquatters.

By paying partners to register typosquatting sites and to send the resulting clicks to Google’s ad platform, Google charges advertisers for traffic they would otherwise have received for free. Google charges advertisers as if these were genuine leads. Yet had typosquatters not registered these domains, ordinary web browsers would have assisted users in reaching advertisers’ sites without charge.

A staggering number of typosquatting web sites target users who misspell the domain names of famous web sites. For example, in my INTA presentation this spring, I showed 200+ typosquatting sites all targeting variations of “cartoonnetwork.com.” I’ll have further thoughts on typosquatting in a future article. But for present purposes, two facts are most important: Typosquatting sites are overwhelmingly funded through pay-per-click ads, and these days Google is the advertising provider of choice for most typosquatters. (My preliminary analysis indicates that Google funds more than 75% of those typosquatting sites that show Google ads.)

Consider a user who misspells comcast.com, instead typing cmcast.com (s.i.c.). Such a user will receive the first screen shown at right, presenting a series of pay-per-click links for Comcast. In all likelihood, such a user will then click a paid link to Comcast — meaning Comcast has to pay Google an advertising fee. Google in turn pays the typosquatter which had the foresight to register a domain. See the packet log.

(In some instances, traffic flows from a typosquatter to one or more brokers or intermediaries, then to Google and finally to the advertiser. As to cmcast.com: The packet log confirms that Google pays MediaLogik of Hong Kong. I cannot readily determine whether MediaLogik registered this domain for its own account, or whether MediaLogik brokers ads for some other registrant. Based on the domain’s hosting in the Bahamas, its monetization through a Hong Kong service provider, and its display of Google PPC ads, it is highly unlikely that this domain was authorized by Comcast.)

Although these typosquatting sites ultimately direct users where the users were trying to go, typosquatters leave targeted advertisers importantly worse-off. Had it not been for the typosquatter, the user would have received a standard browser page identifying the typo and, in general, referring the user to the requested site without charge. See the second screenshot at right, showing a request for cmcast.com in a standard installation of Internet Explorer 6. So, even if no typosquatter had registered cmcast.com, the user would still reach Comcast with equal ease; the typosquatter does not actually make it easier for the user to reach Comcast. But notice that a standard IE6 error page shows few ads — here, just one small ad, at far right — whereas the MediaLogik page showed all ads, front and center. So passing the user’s misspelled request to a standard IE landing page, rather than to a typosquatter, would spare Comcast an expensive Google pay-per-click fee.

Notably, typosquatting exactly fits the traffic pattern detailed in preceding examples. First, Google and its partners identify users who are already trying to reach a given advertiser. Then Google and its partners intercede — here, by registering a typosquatting domain. The user thus stumbles into Google’s ad listings and clicks through to the advertiser’s site — letting Google charge the advertiser a fee, even though the user would have reached the advertiser even without Google’s assistance.

Google Chrome Suggestions Divert Users from Direct Navigation to Search

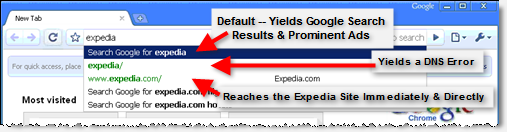

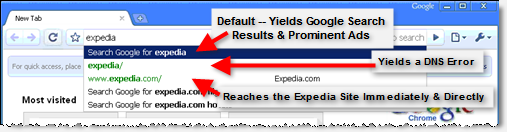

Typing “expedia” yields a suggestion that users search Google (just press “Enter”) rather than visit Expedia.com directly (third entry — requiring a mouse-click or multiple keystrokes). The second link (“expedia/”) yields an error — discouraging future exploration of green direct-navigation listings.

As users type web addresses into Google’s Chrome web browser, Chrome’s “Omnibox” address bar suggests that users run searches instead of direct navigation. See the screenshot at right, showing the Omnibox’s suggestion after I typed “Expedia” and before I typed the final “.com”.

If a user accepts Chrome’s suggestion — by clicking the “Search for …” drop-down, or by merely pressing Enter — the user is taken to a page of Google search results for the specified term. See screenshot and screen-capture video. As usual, Google’s most prominent search result is an advertisement. If the user clicks the ad, the advertiser pays a pay-per-click fee — even though the user was nearly at the advertiser’s site, for free, before Chrome interceded with its “Search for…” suggestion.

To complete a direct navigation to the Expedia site, without passing through Google search results, a user must ignore Google’s suggestion and continue typing (“.com”), click the “expedia.com” entry (third on Google’s autocomplete list), or use the keyboard (down-down-enter) to navigate manually. In principle these steps are straightforward — just a few extra seconds. But by pushing default behavior from direct navigation to search, Google makes searches that much more frequent — yielding that many more ad-clicks, that much more revenue to Google, and that much more expense for advertisers.

Chrome further encourages searching by mixing useful autocomplete direct navigation listings (e.g. “www.expedia.com/”) with nonfunctional listings. Notice that the second entry on Chrome’s autocomplete drop-down is “expedia/” (s.i.c.) — not a valid domain name. If a user clicks that entry, the user suffers a delay followed by a DNS error — hardly a good user experience. (video) By placing this nonfunctional result prominently in the autocomplete drop-down, above the one working direct link to Expedia, and in the same distinctive green font as the working direct link, Chrome discourages users from exploring direct links. After all, if the prominently-listed “expedia/” link did not work, users are less likely to try the similar-looking link Google ranked lower.

Although competing browsers also perform searches if users enter malformed text into the Address Bar, competing browsers are less pushy in suggesting and encouraging searches in lieu of direct navigation. Chrome thus extends browser norms through its increasingly forceful suggestion of search, not direct navigation, as the default way to reach a site.

Beyond its effects on advertisers’ costs, Chrome’s Omnibox raises other serious concerns too. For example, Chrome transmits users’ every navigation keystroke to Google — including what users search for, what addresses users request by name, and what addresses users begin to request but ultimately decline to visit. CNET reports EFF and EPIC staff concerned about Omnibox’s privacy implications, and I share their discomfort.

Fair Play and a Way Forward

Notice similarities across all four examples:

- In all four examples, Google and its partners intercede to divert traffic that, but for their intervention, would reach advertisers’ sites directly — without advertisers incurring any advertising expense.

- In all four examples, Google and its partners ultimately pass the traffic back to the advertisers users were trying to reach — but only after collecting pay-per-click advertising fees.

- In all four examples, if an advertiser attempts to measure its conversion rate, it will conclude that it receives traffic at attractive prices — at effective cost-per-acquisition consistent with its objectives. Standard conversion rate measurements will overlook the fact that, were it not for the intervention of Google and its partners, the advertiser would have received this traffic for free.

Not all advertisers measure conversion rates. For one, some advertisers may take Google at its word, rather than attempting detailed and rigorous monitoring of Google’s effectiveness. Furthermore, for some advertisers, conversion rates are unmeasurable. (Advertisers may have offline sales process, rather than online sales. Certain advertisers may seek brand awareness rather than immediate purchases.) But for advertisers that measure conversion rates and adjust bids accordingly, inflated conversion rates are of grave concern. In particular, inflated conversion rates yield records that seem to indicate that campaigns are working well and delivering fair value, when the truth might be exactly the opposite.

Aggrieved advertisers could sue Google over these placements. But Google imposes terms and conditions that discourage advertisers from pursuing such claims. Google’s Advertising Program Terms purport to “disclaim[] all warranties … [and] guarantees regarding positioning, levels, quality, or timing of costs per click, … clicks, conversions, or any other results” (internal numbering omitted). Google further claims that “Any refunds for suspected invalid impressions or clicks are within Google’s sole discretion.” Google also insists that advertisers’ sole remedy is advertising credits (never refunds), and Google says advertisers must complain within 60 days of a disputed charge (even if advertisers did not know about the improper charges because the charges were concealed through, e.g., inflated conversion rates). I doubt whether all these harsh provisions are enforceable. But if these provisions are enforceable, they would tightly limit advertisers’ ability to obtain redress from Google. Even if these provisions are unenforceable, their mere presence serves to discourage advertisers from filing complaints, whether informal (through Google’s customer service staff) or in court.

In a recent presentation defending its competitive posture and overall approach, Google claimed “advertisers pay what a click is worth to them” (slides 17-21). But does Google have the right to charge such a fee for all traffic, even the traffic advertisers receive without any Google assistance whatsoever? Few advertisers would tolerate such charges, if presented explicitly. Nor does Google ever seek permission to charge advertisers for their existing traffic. Yet in the future Google seems to envision, all manner of ruses intercede to claim Google delivered a customer, when in fact the customer reached the advertiser’s site without bona fide assistance from Google.

More generally, when Google and its partners overstate the effectiveness of the ads they deliver, advertisers cannot make well-informed decisions about which ads to buy or how much to be willing to pay. Danny Sullivan calls AdWords pricing a “black box,” and I certainly share that sentiment. But here, Google’s actions are even worse than opacity: By claiming to have delivered traffic advertisers would have received anyway, Google tricks advertisers into paying for that traffic — and even tricks advertisers into concluding, mistakenly, that the traffic is a good deal.

It’s also hard to reconcile Google’s WhenU and IAC/SmileyCentral placements with Google’s “Software Principles” requirements. With bundled installations disclosing WhenU’s presence only midway through installation, WhenU is anything but “upfront” (contrary to Google’s “upfront disclosure” section heading). Showing the generic “My Web Search” toolbar label after users requested the distinctively-named SmileyCentral, Ask’s offering similarly flunks Google’s call for “clear behavior.” I could continue. But even if these programs satisfied Google’s criteria, they still fall short of advertisers’ reasonable expectations — for they still intercede to claim traffic advertisers they did nothing to deliver.

Looking forward, I see two key principles. First, ad platforms must deliver genuine, incremental traffic — not just intercept and repackage traffic advertisers were already going to receive for free. Second, ad platforms need to stand behind their products — abandoning one-sided attempts to disclaim responsibility, and instead offering meaningful commitments to provide what they promise. In both these respects, Google currently falls short.