Disclosure: I serve as co-counsel in unrelated litigation against Google, Vulcan Golf et al. v. Google et al. I also serve as a consultant to various companies that compete with Google. But I write on my own — not at the suggestion or request of any client, without approval or payment from any client.

Run the Google Toolbar, and it’s strikingly easy to activate “Enhanced Features” — transmitting to Google the full URL of every page-view, including searches at competing search engines. Some critics find this a significant privacy intrusion (1, 2, 3). But in my testing, even Google’s bundled toolbar installations provides some modicum of notice before installing. And users who want to disable such transmissions can always turn them off – or so I thought until I recently retested.

In this article, I provide evidence calling into question the ability of users to disable Google Toolbar transmissions. I begin by reviewing the contents of Google’s "Enhanced Features" transmissions. I then offer screenshot and video proof showing that even when users specifically instruct that the Google Toolbar be “disable[d]”, and even when the Google Toolbar seems to be disabled (e.g., because it disappears from view), Google Toolbar continues tracking users’ browsing. I then revisit how Google Toolbar’s Enhanced Features get turned on in the first place – noting the striking ease of activating Enhanced Features, and the remarkable absence of a button or option to disable Enhanced Features once they are turned on. I criticize the fact that Google’s disclosures have worsened over time, and I conclude by identifying changes necessary to fulfill users’ expectations and protect users’ privacy.

"Enhanced Features" Transmissions Track Page-Views and Search Terms

Certain Google Toolbar features require transmitting to Google servers the full URLs users browse. For example, to tell users the PageRank of the pages they browse, the Google Toolbar must send Google servers the URL of each such page. Google Toolbar’s “Related Sites” and “Sidewiki” (user comments) features also require similar transmissions.

With a network monitor, I confirmed that these transmissions include the full URLs users visit – including domain names, directories, filenames, URL parameters, and search terms. For example, I observed the transmission below when I searched Yahoo (green highlighting) for "laptops" (yellow).

GET /search?client=navclient-auto&swwk=358&iqrn=zuk&orig=0gs08&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8&querytime=kV&querytimec=kV &features=Rank:SW:&q=info:http%3a%2f%2frds.yahoo.com%2f_ylt%3dA0oGkl32p1tLT2EB8ohXNyoA%2fSIG%3d18045klhr%2f

EXP%3d1264384374%2f**http%253a%2f%2fsearch.yahoo.com%2fsearch%253fp%3dlaptops%2526fr%3dsfp%2526xargs%3d12KP

jg1itSroGmmvmnEOOIMLrcmUsOkZ7Fo5h7DOV5CtdY6hNdE%25252DIfXpP0xZg6WO8T7xvSy7HBreVFdJGu277WVk0qfeG%25255FGOW%2

5255F772GnNVme5ujWkF3s%25252DJ%25255F0%25252Dmdn4RvDE8%25252E%2526pstart%3d7%2526b%3d11&googleip=O;72.14.20

4.104;226&ch=711984234986 HTTP/1.1

User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; GoogleToolbar 6.4.1208.1530; Windows XP 5.1; MSIE 8.0.6001.18702)

Accept-Language: en

Host: toolbarqueries.google.com

Connection: Keep-Alive

Cache-Control: no-cache

Cookie: PREF=ID=…

HTTP/1.1 200 OK …

Screenshots – Google Toolbar Continues Tracking Browsing Even When Users "Disable" the Toolbar via Its "X" Button

Consistent with modern browser plug-in standards, the current Google Toolbar features an “X” button to disable the toolbar:

I clicked the “X” and received a confirmation window:

I chose the top option and pressed OK. The Google Toolbar disappeared from view, indicating that it was disabled for this window, just as I had requested. Within the same window, I requested the Whitehouse.gov site:

Although I had asked that the Google Toolbar be "disable[d] … for this window " and although the Google Toolbar disappeared from view, my network monitor revealed that Google Toolbar continued to transmit my browsing to its toolbarqueries.google.com server:

See also a screen-capture video memorializing these transmissions.

These Nonconsensual Transmissions Affect Important, Routine Scenarios (added 1/26/10, 12:15pm)

In a statement to Search Engine Land, Google argued that the problems I reported are "only an issue until a user restarts the browser." I emphatically disagree.

Consider the nonconsensual transmission detailed in the preceding section: A user presses "x", is asked "When do you want to disable Google Toolbar and its features?", and chooses the default option, to "Disable Google Toolbar only for this window." The entire purpose of this option is to take effect immediately. Indeed, it would be nonsense for this option to take effect only upon a browser restart: Once the user restarts the browser, the "for this window" disabling is supposed to end, and transmissions are supposed to resume. So Google Toolbar transmits web browsing before the restart, and after the restart too. I stand by my conclusion: The "Disable Google Toolbar only for this window" option doesn’t work at all: It does not actually disable Google Toolbar for the specified window, not immediately and not upon a restart.

Crucially, these nonconsensual transmissions target users who are specifically concerned about privacy. A user who requests that Google Toolbar be disabled for the current window is exactly seeking to do something sensitive, confidential, or embarrassing, or in any event something he does not wish to record in Google’s logs. This privacy-conscious user deserves extra privacy protection. Yet Google nonetheless records his browsing. Google fails this user — specifically and unambiguously promising to immediately stop tracking when the user so instructs, but in fact continuing tracking unabated.

Google Toolbar Continues Tracking Browsing Even When Users "Disable" the Toolbar via "Manage Add-Ons"

Internet Explorer 8 includes a Manage Add-Ons screen to disable unwanted add-ons. On a PC with Google Toolbar, I activated Manage Add-Ons, clicked the Google Toolbar entry, and chose Disable. I accepted all defaults and closed the dialog box.

Again I requested the whitehouse.gov site. Again my network monitor revealed that Google Toolbar continued to transmit my browsing to its toolbarqueries.google.com server. Indeed, as I requested various pages on the whitehouse.gov site, Google Toolbar transmitted the full URLs of those pages, as shown in the second and third circles below.

See also a screen-capture video memorializing these transmissions.

In a further test, performed January 23, I reconfirmed the observations detailed here. In that test, I demonstrated that even checking the "Google Toolbar Notifier BHO" box and disabling that component does not impede these Google Toolbar transmissions. I also specififically confirmed that these continuing Google Toolbar transmissions track users’ searches at competing search engines. See screen-capture video.

In my tests, in this Manage Add-Ons scenario, Google Toolbar transmissions cease upon the next browser restart. But no on-screen message alerts the user to the need for a browser-restart for changes to take effect, so the user has no reason to think a restart is required.

Google Toolbar Continues Tracking Browsing When Users "Disable" the Toolbar via Right Click (added 1/26/10 11:00pm)

Danny Sullivan asked me whether Google Toolbar continues Enhanced Features transmissions if users hide Google Toolbar via IE’s right-click menu. In a further test, I confirmed that Google Toolbar transmissions continue in these circumstances. Below are the four key screenshots: 1) I right-click in empty toolbar space, and I uncheck Google Toolbar. 2) I check the final checkbox and choose Disable. 3) Google Toolbar disappears from view and appears to be disabled. I browse the web. 4) I confirm that Google Toolbar’s transmissions nonetheless continue. See also a screen-capture video.

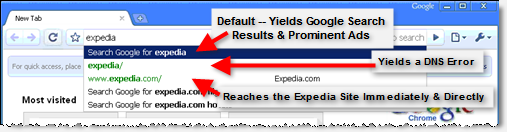

Users May Easily or Accidentally Activate “Enhanced Features” Transmissions

Google Toolbar invites users to activate Enhanced Features with a single click, the default. Also, notice self-contradictory statements (transmitting ‘site’ names versus full ‘URL’ adresses).

Google Toolbar invites users to activate Enhanced Features with a single click, the default. Also, notice self-contradictory statements (transmitting ‘site’ names versus full ‘URL’ adresses).

The above-described transmissions occur only if a user runs Google Toolbar in its “Enhanced Features” mode. But it is strikingly easy for a user to stumble into this mode.

For one, the standard Google Toolbar installation encourages users to activate Enhanced Features via a “bubble” message shown at the conclusion of installation. See the screenshot at right. This bubble presents a forceful request for users to activate Sidewiki: The feature is described as “enhanced” and “helpful”, and Google chooses to tout it with a prominence that indicates Google views the feature as important. Moreover, the accept button features bold type plus a jumbo size (more than twice as large as the button to decline). And the accept button has the focus – so merely pressing Space or Enter (easy to do accidentally) serves to activate Enhanced Features without any further confirmation.

I credit that the bubble mentions the important privacy consequence of enabling Enhanced Features: “For enhanced features to work, Toolbar has to tell us what site you’re visiting by sending Google the URL.” But this disclosure falls importantly short. For one, Enhanced Features transmits not just “sites” but specific full URLs, including directories, filenames, URL parameters, and search keywords. Indeed, Google’s bubble statement is internally-inconsistent – indicating transmissions of “sites” and “URLs” as if those are the same thing, when in fact the latter is far more intrusive than the former, and the latter is accurate.

The bubble also falls short in its presentation of Google Toolbar’s Privacy Policy. If a user clicks the Privacy Policy hyperlink, the user receives the image shown in the left image below. Notice that the Privacy Policy loads in an unusual window with no browser chrome – no Edit-Find option to let a user search for words of particular interest, no Edit-Select All and Edit-Copy option to let a user copy text to another program for further review, no Save or Print options to let a user preserve the file. Had Google used a standard browser window, all these features would have been available, but by designing this nonstandard window, Google creates all these limitations. The substance of the document is also inapt. For one, “Enhanced Toolbar Features” receive no mention whatsoever until the fifth on-screen page (right image below). Even there, the first bullet describes transmission of “the addresses [of] the sites” users visit – again falsely indicating transmission of mere domain names, not full URLs. The second bullet mentions transmission of “URL[s]” but says such transmission occurs “[w]hen you use Sidewiki to write, edit, or rate an entry.” Taken together, these two bullets falsely indicate that URLs are transmitted only when users interact with Sidewiki, and that only sites are transmitted otherwise, when in fact URLs are transmitted whenever Enhanced Features are turned on.

Certain bundled installations make it even easier for users to get Google Toolbar unrequested, and to end up with Enhanced Features too. With dozens of Google Toolbar partners, using varying installation tactics, a full review of their practices is beyond the scope of this article. But they provide significant additional cause for concern.

Enhanced Features: Easy to Enable, Hard to Turn Off

The preceding sections shows that users can enable Google Toolbar’s Enhanced Features with a single click on a prominent, oversized button. But disabling Enhanced Features is much harder.

The preceding sections shows that users can enable Google Toolbar’s Enhanced Features with a single click on a prominent, oversized button. But disabling Enhanced Features is much harder.

Consider a user who changes her mind about Enhanced Features but wishes to keep Google Toolbar in its basic mode. How exactly can she do so? Browsing the Google Toolbar’s entire Options screen, I found no option to disable Enhanced Features. Indeed, Enhanced Features are easily enabled with a single click, during installation (as shown above) or thereafter. But disabling Enhanced Features seems to require uninstalling Google Toolbar altogether, and in any event disabling Enhanced Features certainly lacks any comparably-quick command.

I’m reminded of The Eagles’ Hotel California: "you can check out anytime you like, but you can never leave." And of course, as discussed above, a user who chooses the X button or Manage Add-Ons, will naturally believe the Google Toolbar is disabled, when in fact it continues transmissions unabated.

Google Toolbar Disclosures Have Worsened Over Time

I first wrote about Google Toolbar’s installation and privacy disclosures in my March 2004 FTC comments on spyware and adware. In that document, I praised Google’s then-current toolbar installation sequence, which featured the impressive screen shown at right.

I praised this screen with the following discussion:

I consider this disclosure particularly laudable because it features the following characteristics: It discusses privacy concerns on a screen dedicated to this topic, separate from unrelated information and separate from information that may be of lesser concern to users. It uses color and layout to signal the importance of the information presented. It uses plain language, simple sentences, and brief paragraphs. It offers the user an opportunity to opt out of the transmission of sensitive information, without losing any more functionality than necessary (given design constraints), and without suffering penalties of any kind (e.g. forfeiture of use of some unrelated software). As a result of these characteristics, users viewing this screen have the opportunity to make a meaningful, informed choice as to whether or not to enable the Enhanced Features of the Google Toolbar.

I stand by that praise. But six years later, Google Toolbar’s installation sequence is inferior in every way:

- Now, initial Enhanced Features privacy disclosures appear not in their own screen, but in a bubble pitching another feature (Sidewiki). Previously, format (all-caps, top-of-page), color (red) and language ("… not the usual yada yada") alerted users to the seriousness of the decision at hand.

- Now, Google presents Enhanced Features as a default with an oversized button, bold type, and acceptance via a single keystroke. Previously, neither option was a default, and both options were presented with equal prominence.

- Now, privacy statements are imprecise and internally-inconsistent, muddling the concepts of site and URL. Previous disclosures were clear in explaining that acceptance entails "sending us [Google] the URL" of each page a user visits.

- The current feature name, "Enhanced Features," is less forthright than the prior "Advanced Features" label. The name "Advanced Features" appropriately indicated that the feature is not appropriate for all users (but is intended for, e.g., "advanced" users). In contrast, the current "Enhanced Features" name suggests that the feature is an "enhancement" suitable for everyone.

Google’s Undisclosed Taskbar Button

The Google Toolbar also added a “Google” button to my Taskbar, immediately adjacent to the Start button. The Toolbar installer added this button without any disclosure whatsoever in the installation sequence – not on the toolbar.google.com web page, not in the installer EXE, not anywhere else.

An in-Taskbar button is not consistent with ordinary functions users reasonably expect when they seek and install a “toolbar.” Because this function arrives on a user’s computer without notice and without consent, it is an improper intrusion.

Google’s first step is simple: Fix the Toolbar so that X and Manage Add-Ons in fact do what they promise. When a user disables Google Toolbar, all Enhanced Features transmissions need to stop, immediately and without exception. This change must be deployed to all Google Toolbar users straightaway.

Google also needs to clean up the results of its nonconsensual data collection. In particular, Google has collected browsing data from users who specifically declined to allow such data to be collected. In some instances this data may be private, sensitive, or embarrassing: Savvy users would naturally choose to disable Google Toolbar before their most sensitive searches. Google ordinarily doesn’t let users delete their records as stored on Google servers. But these records never should have been sent to Google in the first place. So Google should find a way to let concerned users request that Google fully and irreversibly delete their entire Toolbar histories.

Even when Google fixes these nonconsensual transmissions, larger problems remain. The current Toolbar installation sequence suffers inconsistent statements of privacy consequences, with poor presentation of the full Toolbar Privacy Statement. Toolbar adds a button to users’ Taskbar unrequested. And as my videos show, once Google puts its code on a user’s computer, there’s nothing to stop Google from tracking users even after users specifically decline. I’ve run Google Toolbar for nearly a decade, but this week I uninstalled Google Toolbar from all my PCs. I encourage others to do the same.